Poison Ivy

Watch out for Poison Ivy!

Poison ivy is a natural component of the dune ecology and is also a frequent weed in yards and along the edges of roads and paths. Long Beach Island and the surrounding pinelands and coastal forests are prime areas for poison ivy. The best way to avoid rash and discomfort of poison ivy is to avoid the plant.

Spotting poison ivy

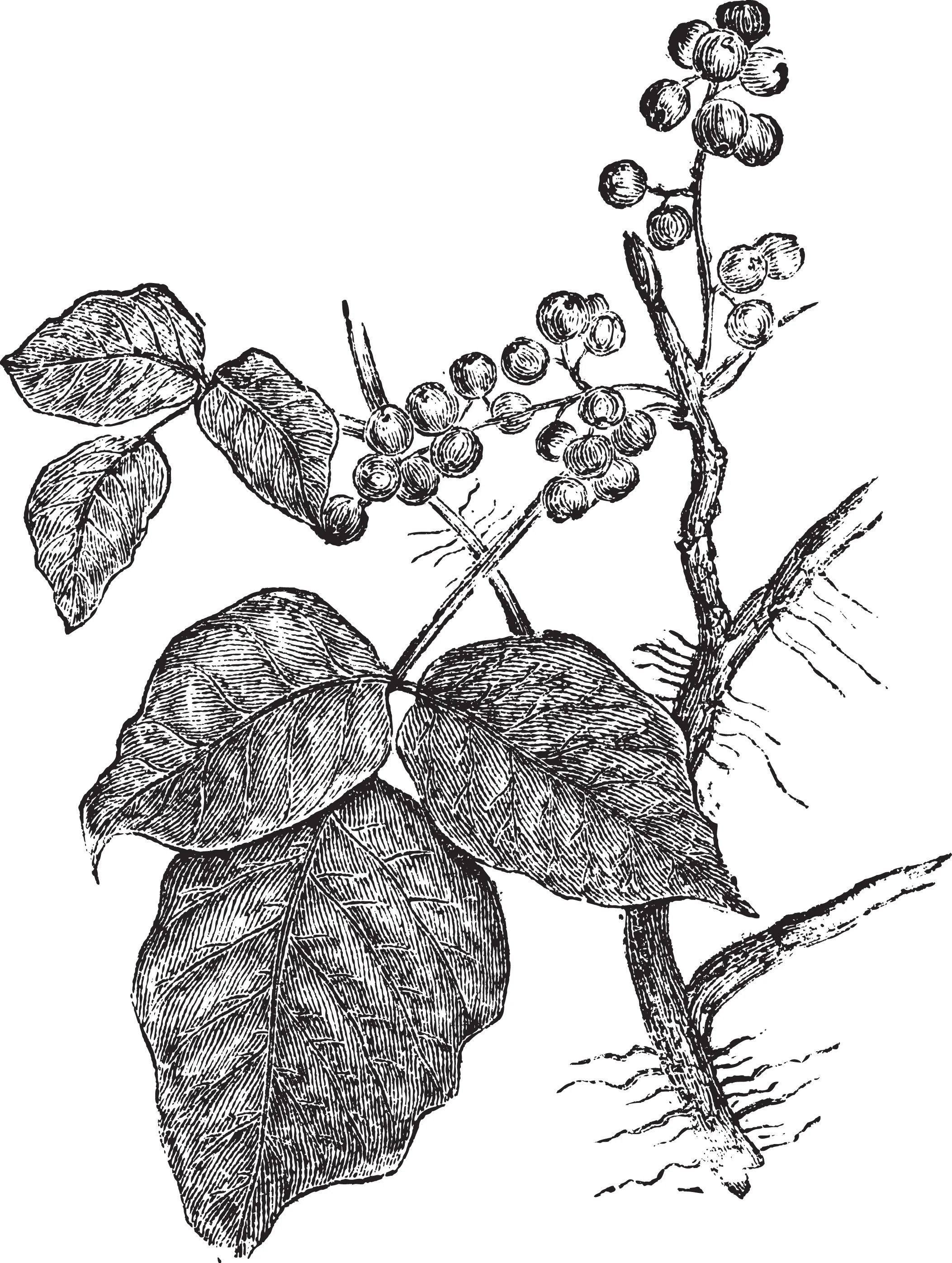

“Leaflets three let it be!” The leaves of poison ivy are always in threes, two leaflets are split by a third, which is on a slightly longer stem. New leaves will be tiny and red or maroon colored, older leaves are usually shiny, and dark green. The shape of the individual leaves varies from smooth to notched to lobed. The leaves will never be serrated like a saw blade.

In fall the leaves of poison ivy become bright red. In winter the vines of poison ivy will appear as hairy rope running up the sides of trees and fence posts. The seeds of poison ivy are in grey berries that frequently hang on in loose clusters through out the winter. These berries may be eaten by birds and then spread from one location to another. This is why poison ivy will appear under your trees or along fence lines—all under places birds perch.

What makes poison ivy poison?

The oil in poison ivy, urushiol (u-roo-she-al), causes contact dermatitis (an itchy rash) in a large percentage of the population, although the severity of this can vary widely from person to person. Itchiness begins about 24 hours after exposure and can last over 3 weeks! In severe cases the rash will continue to grow over this period, leading to the misconception that scratching will spread the rash. Actually your body is just continuing to react to the first exposure.

Urushiol is present in every part of the poison ivy plant—the roots, the stems, and the leaves all have this oil on the inside and outside of the plant.

Exposure

Urushiol will stick to anything that comes in contact with the plant, including your skin, cloths, gloves, tools, shoes, and the ball that got kicked over the fence! The oil will not spread through the air unless poison ivy is burned. Inhaling smoke from burning poison ivy can cause serious, even fatal reactions. Mystery exposure is usually the result of contact with garden tools that came into contact with poison ivy (the oil can stay on garden tools for years) or carrying firewood into the house. Animals are not bothered by poison ivy, but the oil on their fur can affect a person who pets them.

Those that seem immune to poison ivy today should not count on that immunity, sensitivity can and often does change over time.

Treatment

If you know that you have been exposed to poison ivy, repeated washing with cold water and soap or with Tecnu (available at drug stores) will remove the oil from your skin. Clothing should be laundered separately, or dry cleaned (it is only fair to tell the dry cleaner about the poison ivy!). Tools that have been in contact with the plant should be assumed to be contaminated and washed repeatedly with soap and water. Chemical control is best left up to a licensed professional. A severe infection warrants a visit to a doctor.

Keep in mind that poison ivy is one of the few native plants that still thrive on Long Beach Island. An old timer in Barnegat Light once told me that poison ivy is what “holds the island together in a storm”; he may not have been wrong. If the plant is not growing in an area where it is likely to contact people it should be left undisturbed.